Why Trump Won

When Donald Trump first ran for President in 2000, he was widely dismissed, and never made it to the primary. By 2016 the United States was fertile soil for a candidate like him. In this edition of the newsletter I explain why.

The best analysis of how the US was shifting during that time was captured in 2009 by Harvard Economist Claudia Goldin. The result of last week’s election is the culmination of a long-brewing, slow-moving economic storm that is now making landfall. Goldin wrote about these innovation and economic undercurrents in her 2009 book “The Race Between Technology and Education”.

The Goldin Rule And The Great Bifurcation

Goldin found that huge leaps in innovation sometimes cause widespread prosperity and other times cause economic instability. The key variable, Goldin found, is education. When innovation is accompanied by equivalent improvements in education it creates widespread prosperity. When innovation outpaces education it exacerbates inequality and drives inequality and economic instability. (Goldin measures innovation through total factor productivity, which calculates how much money a country generates per dollar spent, hour worked, and energy consumed - when we make more money with less stuff we’re innovating well and TFP improves. She measures education by the percentage of Americans who graduate with advanced degrees by year of birth).

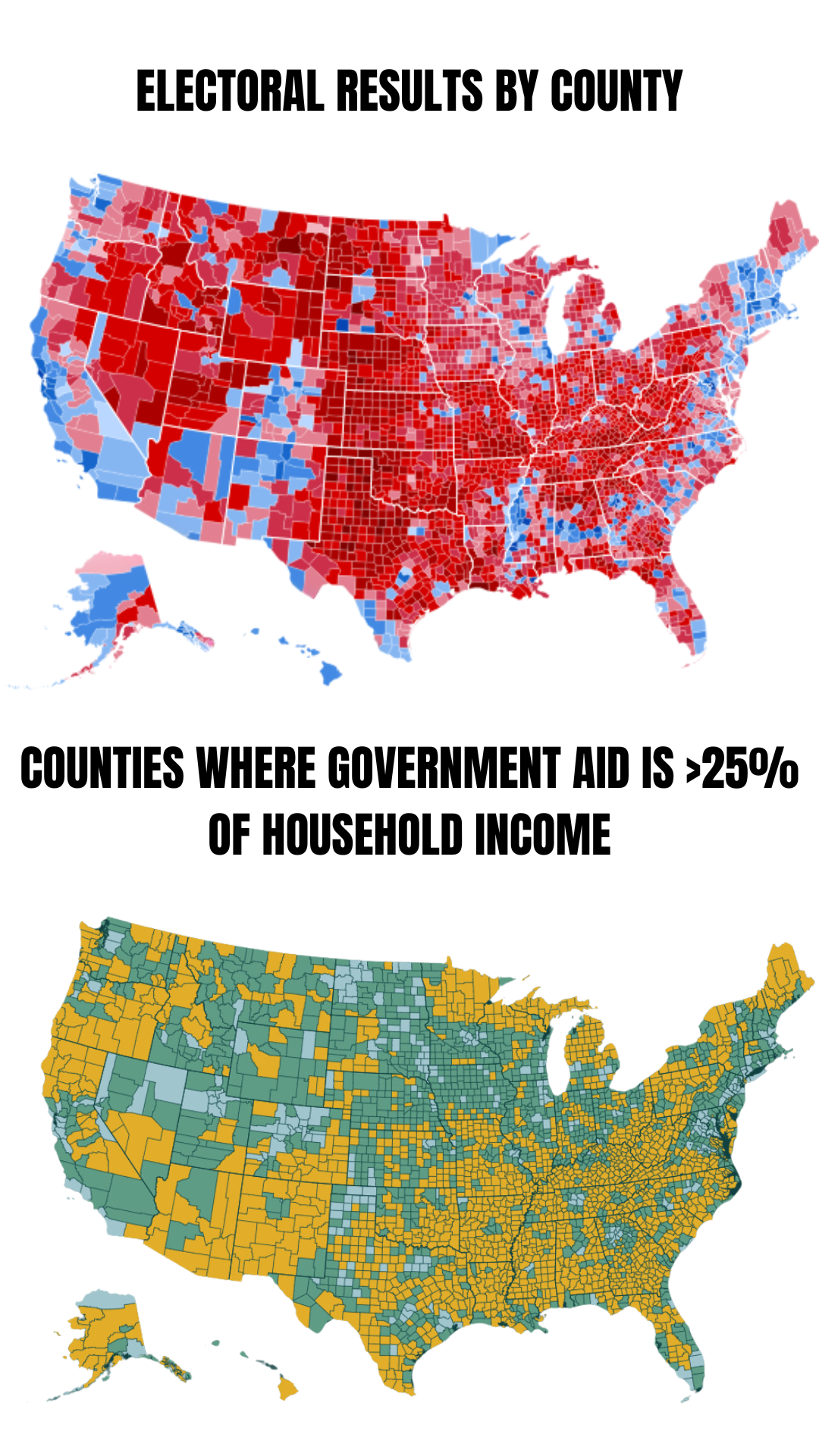

We’re currently 40 years deep into a dangerous cycle of education stagnation and innovation acceleration that has created rampant inequality. American schools are not preparing students for the highest paying, most in-demand careers. The few people who have the most in-demand skills, make more money than everyone else and are geographically concentrated in a few metropolitan areas which consistently vote Democrat.

From 1900 - 1975, it was different. Breakthroughs in cars, aerospace, communications technology, and energy were accompanied by massive improvements in education. Most Americans made more money and had better education than their parents. Most Americans graduated from school with skills that were highly in demand by the fastest growing companies and industries.

After 1975, and especially after the internet emerged in the 1990s, innovation exacerbated inequality. The skills that make the most money in the digital age were not taught in most schools. They still aren’t. My generation, Gen X, is the first generation since 1900 in which the average American made less money and attained less education than their parents.

What happened last Tuesday was an inevitable byproduct of an unprecedented innovation bifurcation of the American economy. Donald Trump just happened to be its beneficiary. The innovation education imbalance that Goldin observed in 2009, is a gigantic Tsunami today.

Righteous Indignation

Because of the massive innovation and economic divide between these two Americas, our elections are increasingly battles of class warfare between the interior and the coasts. The candidate who can aggravate the sense of economic injustice wins.

And much of America has every right to feel a sense of economic injustice.

We have become a nation that is simultaneously in the throes of deep decay and astounding leaps forward all at the same time.

We mint billionaires who make teenagers more addicted to their screens. We create investment banks that cause subprime mortgage calamities.

But it takes more labor, time, and energy to produce a mile of highway, file an insurance claim, or receive healthcare than in the 1980s.

Manufacturing labor productivity is down 5% since 2011 after doubling every twenty years since about 1900 (source: St. Louis Federal Reserve).

Income inequality in America is at its highest level since the 1920s.

In 2022, Americans received $3.8 trillion in financial aid from the government, roughly $11,500 per person. Government assistance now accounts for nearly 18% of household income. In 1970 less than 2% of the population depended on government aid.

Tuition at private, four-year colleges has increased by 184% over the past 20 years, making education even less attainable, exacerbating the innovation-education imbalance that Goldin identified.

This election wasn’t even really about inflation. Inflation was a convenient symbol of an economy that produces workers that are no longer relevant for the companies and industries which thrive today in most of the country.

This blog post might sound like a rant. I hope it’s actually a call to action.

1. Build Better Schools for More People / Why the fuck do my kids have the same high school curriculum as I did in 1995?

I graduated from high school before email was widespread, the internet was just emerging, and no one except the douchebags on Wall Street had cell phones. Chat GPT, Google, the iPhone, bitcoin, Amazon, and Tesla are a few top-of-mind transformative innovations that hadn’t emerged back then. How people make money today is completely different. And yet my kids’ high school curriculum is pretty much the exact same as mine. Every high school graduate should know how to build a website, a product roadmap, a marketing campaign, get meetings with influential people, file a tax return, be fluent in a second language, run a correlation, and build a discounted cashflow model. Trigonometry, algebra, and calculus may feed into those baseline skills, but I have no idea how. If someone applied for a job with an A in trigonometry and none of these other skills I wouldn’t hire them and neither would you. In whatever sphere of influence you have: your kids’ school, your alma mater, the school where your friend is a teacher, go agitate for relevant education.

2. Teach agility.

In our adult lives we learn through coding bootcamps, agile certifications, and valuation seminars that are 1-3 intensive days. We learn agility. When we see what we don’t know we fill in the gaps as quickly as possible. Many of the best developers, engineers, and designers I worked with at Google and Uber never went to college; they couldn’t afford it, or didn’t see the point. So they learned how to add value in other ways. I contrast this with the way my kids are taught: one year of algebra, another of calculus, another of geometry. This is not a zero-sum argument that we should abolish deep, PhD level expertise in a narrow field. But that should be an option rather than a default. Learning agility is deeply undervalued and undertaught.

3. Hire for hunger - not pedigree.

Or, more specifically, don’t make college graduation a prerequisite for employment. Hire for scraptitude. Hire people who are poor, hungry, and determined. Hire people who have done ingenious, creative things to fill the gaps in their education.